The Lean Product Process: #2 Formulating Your Value Proposition

Those of you, who did not read my previous article, should know that we are building a product. Well, a hypothetical one, to illustrate the different stages of lean product development.

This product is a gadget equipped with different sensors mounted on micromobility devices, like a bicycle, an e-scooter or even a skateboard. When approaching an obstacle or detecting danger (such as a vehicle, pedestrian, crossing, etc.), our gadget will emit sound and vibration alerts, helping us travel safely.

In the previous article, we already determined what assumptions (problem hypothesis) we need to answer in the problem validation stage. I also showed you the available tools to test these assumptions.

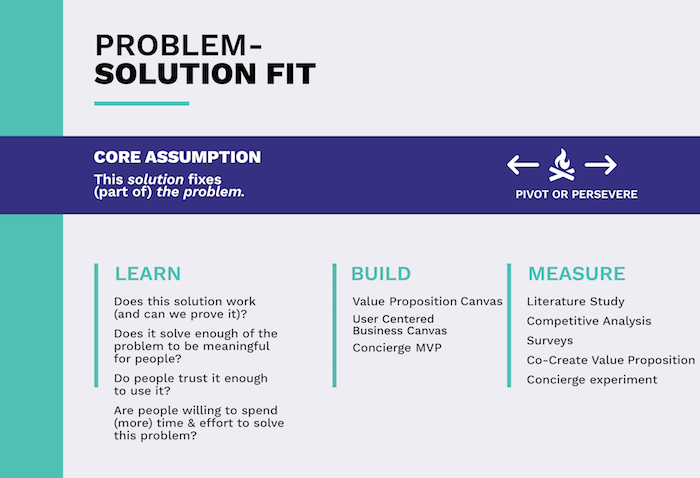

Our next step will be proving the problem-solution fit. When entering this stage, in the Learn phase of our loop, we'll be looking to demonstrate the following assumptions:

- our product helps the user be safer when travelling

- our product improves the sense of safety of users in such a way that would incentivise them to use the gadget regularly

We call these assumption value hypotheses. As the name implies, the value hypothesis proved that our solution brings added value for our users.

Formulating our value proposition

In the problem validation stage, we probably discovered many user pain points and hopefully just as many opportunities to improve our users' daily lives. If our product manages to soothe these pain points and deliver these improvements, then our value propositions will be valid, and our problem-solution fit proven. Let us see what steps we can take to achieve this.

Value proposition canvas

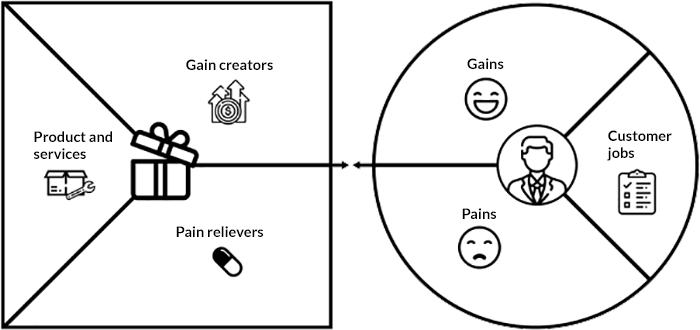

One of the most useful tools to prove problem-solution fit is the value proposition canvas, introduced by Alex Osterwalder and co., in their book titled Value Proposition Design. The canvas is as simple as it gets: it's made of 1 square and 1 circle.

We begin filling our canvas with the circle, which contains our observations of our target audience. The circle (user profile) is sliced into 3 subsections:

- Customer jobs - functional (I want to get from A to B), emotional (I feel safe) and social (I look good while travelling) actions that our users perform.

- Pains - obstacles, negatives and frustrations that our user would rather avoid.

- Gains - positive outcomes, added value, or desires that our user longs for.

We can source this information from the user personas we created in the problem validation stage, as the assumptions we set when creating the personas have been already confirmed (or contradicted) by the user interviews. You did update your personas after the interviews, did you?

If we have several personas, we will have multiple value proposition canvases since we have a different value proposition for each user group. Write down each job, pain point and gain on a post-it note and stick it in the correct space on the canvas. If you wish to create a digital canvas, I recommend using Miro.

When done with the circle, we can move on to the square, called the value map in the Value Proposition Design, which is also split into 3 subsections:

- Products and services - the services and products that deliver our value proposition. In our case, this can be the gadget itself, the companion mobile app (because you must have one, don't you?), or even customer support.

- Pain relievers - the pain points that the above services or products relieve or how they improve users' lives.

- Gain creators - the gains delivered by the above services or products or how they improve results for users.

Scribble them on a post-it and paste them onto the canvas. Compare the pain points and gains under the user profile (circle) with the pain relievers and gain creators under the value map (square). Do they match? If so, then we (probably) have a product-solution fit.

If they don't match, we should look at the canvas more closely. Pain relievers and gain creators that don't have a corresponding item under the user profile are probably answers to user needs that don't exist. Hence they are superfluous.

On the other hand, if some pain points or gains don't correlate on the value map, it's a good indicator that the service or product needs more thought.

We can also prioritise pain points and gains. We should, by now, based on the interviews, have a pretty good understanding of which are the most important to our users. If some pains or gains are repeated across multiple user groups (personas), that is an excellent reason to prioritise them. We should concentrate on the essentials and iterate until a correlation between the user profile and value map is achieved.

We can fill a value proposition canvas as a team, but as with journey maps, it's much more exciting to co-create it together with potential users.

User-centred business canvas

Another canvas… I think it's getting pretty apparent by now that I love canvases.

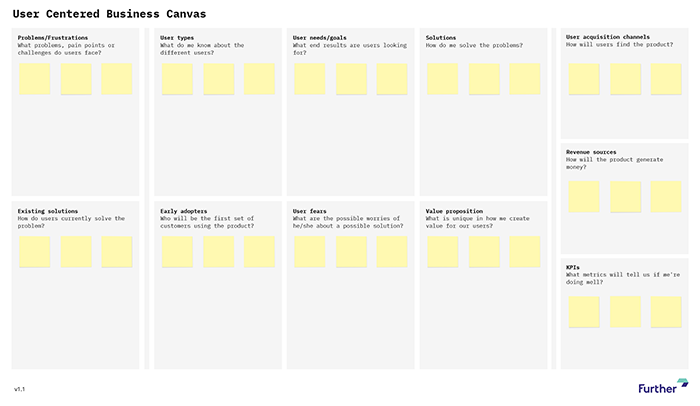

I first learned of the user-centred business canvas from Csaba Házi's UX Kitchen podcast and immediately started using it, albeit with a couple of tweaks. The canvas structure closely resembles Alex Osterwalder's other famous canvas, the business model canvas, and Ash Maurya's lean canvas. This resemblance isn't by accident, as they heavily influenced the UCBC. But while the former is much more business-focused and the latter problem and product-focused, the UCBC puts the relation between user needs and solution front and centre.

But let us see what this canvas is all about. We can see 11 cells split into 3 distinct sections. The leftmost 2 cells describe our problem, the middle 6 describe the relationship between user and solution, while the rightmost 3 are all about the business aspects. These 3 sections create an easy to follow product development curve, all the way from problem validation to product-market fit.

We already know the answers to the problem section from the user interviews in the problem validation stage. We input the user problems, pain points and challenges in the top cell and the existing solutions in the bottom cell. These can be competitors, but also methods our users currently employ to solve their problems. In our case, these will be the other safety gadgets on the market.

The middle section will also be familiar. The user types are basically our personas. The user needs/goals and fears cells we can also find in our personas.

I must, however, talk a bit about early adopters. Geoffrey Moore popularised the term early adopter in his book title Crossing the Chasm. Moore identified 5 distinct user types based on how likely they are to start using new technologies (or products).

These are the innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and the laggards. Moore observed that for most new technologies (especially disruptive technologies), it's exponentially harder to reach (or to market to) the early majority compared to the early adopters. Hence the chasm.

To test our product, we must first convince our early adopters. They will be the key to reaching the majority, which is why they have an important space on our canvas.

We reach the solutions and value proposition cells as we advance with our canvas. Luckily, we already have these filled in our value proposition canvas!

The final 3 cells describe business aspects, which we won't cover in the problem-solution stage. But they should be pretty self-explanatory.

The UCBC, just as the personas or the user interviews, is a tool we can use throughout the different stages of product development. Sometimes I start with the UCBC and use it to build my personas and value proposition. But most often, I first use it in the problem-solution fit stage.

Testing our value proposition

By merely tinkering with our value proposition until we correlate the user profile and value map, we haven't yet proven our value hypothesis, and we cannot yet talk about a problem-solution fit. We have to test this correlation. Note that if we co-created the value proposition with potential users, we have already made a small step in the right direction.

You could ask yourself the question, and rightly so, how we can test our assumptions without a product? Luckily enough, some more tools in our arsenal can help.

Surveys

Probably the most widely used validation tool is the survey. While the user interviews count as a qualitative tool, surveys are quantitative.

Many product teams wrongly use surveys in the problem validation stage as a substitute for interviews. The problem with this is that it assumes we already know the questions we need to ask of our users. Furthermore, because you also need to offer response options, it assumes we already know the answers. As we learned from the last article, the problem validation stage focuses on discovering the unbeknown. And for that purpose, interviews are a much more suitable tool since we can ask follow up questions and dig deeper.

But while surveys are not suitable in the early stages, they are much more effective in confirming the knowledge we have already acquired. In his book titled The Lean Product Playbook, Dan Olsen calls this doing quant on qual, which means is doing quantitative research and qualitative data.

Let's create a survey that tests our value proposition. Do our pain relievers soothe the pain points? Do the gain creators deliver the expected results?

In the case of our product, we might ask respondents to rate on a scale of 5 how likely they would be to trust such a gadget or how important they consider their safety to be in relation to that of others (like pedestrians). We could even ask which functions they would rather control via the gadget's touch screen or buttons and which we could hide inside the companion app.

Debunking all the secrets of the art of surveying is beyond the scope of this article. Still, if I had to point out, one thing everyone should consider is including filter questions at the beginning of your survey. These questions allow us to filter out non-relevant responders.

In the case of our product, responders who never use micromobility devices will not be relevant to us. Similarly, opinions of those who only use them in controlled, safe environments like skate parks will be less applicable. We should ask them preliminary questions like how often they use micromobility devices? Where do they use them (in what context)?

When compiling preliminary questions, we can turn to personas again (I told you they'd become useful later on as well). If we have multiple personas, consider creating several personalised surveys.

Concierge experiment

Another technique to test our value proposition is the concierge experiment. This experiment involves selecting a couple of users for whom we provide a similar user experience as the end product would do while implementing the functions manually in the background. Basically, we replace a complex technical solution with humans.

Obviously, this experiment doesn't work for every type of product. Let's take our product idea, for example. Unless we want to run after an electric scooter, shouting at the operator when we spot danger, it's hard to see how we might implement this experiment. More importantly, it's also pretty far from the expected user experience.

The best-known concierge experiment is Manuel Rosso's Food on the Table project, which Eric Ries also mentioned in his The Lean Startup book. Manuel's vision was a digital product that would take into account the eating habits of users and the different discounts at local stores and compile a weekly meal plan and grocery list.

Instead of jumping in and developing the software, Manuel chose to experiment first. He picked 1 user (!) and spent some time understanding her eating habits and favourite recipes. He delivered her the groceries every week, together with a recipe list that she could create from those groceries. He asked the lady's opinion of the recipes, which allowed him to improve his service, and more importantly, he took a check for $9.95.

Of course, this was not profitable and nowhere near a scalable business. But Manuel did gain valuable new information week in, week out. Soon, he expanded his customer base with a couple of new users. The simple fact that these users were willing to pay for this service every time they knocked on their door proved their value proposition.

Conclusions

When starting our search for the problem-solution fit, we were looking to prove the following assumptions:

- our product helps the user be safer when travelling

- our product improves the sense of safety of users in such a way that would incentivise them to use the gadget regularly

Our first step was to define our value proposition. This step can be done by (co-)creating a value proposition canvas. A user-centred business canvas can help visualise the user needs and possible solutions.

These tools help us define, structure and visualise, but they are not enough to prove our assumptions. To do that, we can use surveys or a concierge experiment if the nature of our product allows it.

Once we manage to prove our assumptions, we can proceed to our solution-product fit stage. Otherwise, we can always pivot.

If you liked this article, download the accompanying infographic!

I want the infographic