The Lean Product Process: #1 Understanding Your Customers

In my college years, I frequently asked myself: why do we need to study so much theory. Why isn't there more practical learning? Although I still maintain my opinion that the ratio of theoretical vs practical learning is disproportionate, I came to realise that you can't practice without strong theoretical grounds.

In my previous article, I laid out the theory. We learned about the build-measure-learn loop, validation and the different stages of product development. The good news is that, from here on, we're going to get more hands-on.

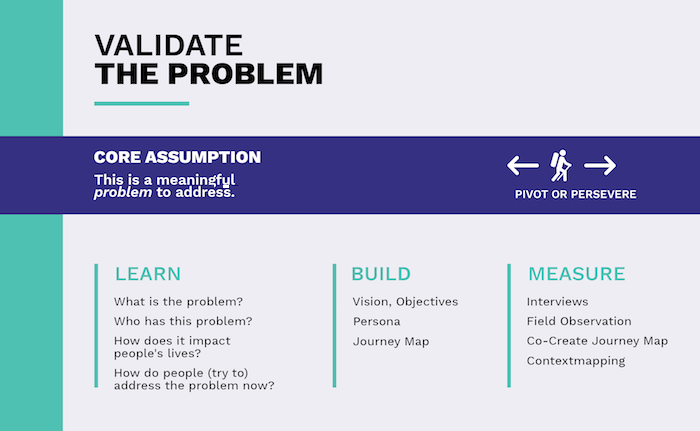

In the next couple of articles, I will take a closer look at the different stages of product development and demonstrate the build-measure-learn loop and available tools for each one. Let's jump in straight away and start with the problem validation phase.

The vision

It all starts with a vision — a product that will solve one or more problems for one or more target groups. For illustration purposes, let's make up a product: a gadget that makes travelling safer for users of micromobility vehicles, both motorised and non-motorised.

A product that can be attached to a bike, electric scooter, or even a Segway gives us audible and tactile (through vibration) alerts if it senses an obstacle (pedestrian, crossing, vehicle, etc.) thanks to its hundreds of sensors. Now, I don't know if such a product already exists or not. I also don't know if building such a product is feasible at this point in time. But for the sake of this exercise, let's assume that it doesn't exist and all the technical prerequisites are given.

For the product to be successful, we have to prove several hypotheses. Let's break up our vision into the following hypotheses:

- each (motorised and non-motorised) micromobility user faces this (safety) problem

- users of micromobility vehicles do not feel safe when travelling and would like to be able to travel in a safer way

- users of micromobility vehicles are not happy with the current safety solutions

- our product helps the user be safer when travelling

- our product improves the sense of safety of users in such a way that would incentivise them to use the gadget regularly

- our product is easy to use

- our users trust the product

- users are still willing to pay or exchange value for our product or service

- we can keep our existing users, maybe even sell the additional products or services

- our users like the product enough to recommend it to others

Those experienced in lean product development have probably already noticed that some of these hypotheses are slightly lamish. That's on purpose. I tried to formulate our assumptions in a way that a product development team who are at their first rodeo would do. We'll reformulate these assumptions later on. My goal right now is to show a path to a successful product and ways to treat the inevitable bumps and obstacles on that path.

In the Learn phase (of our build-measure-learn loop) of the first stage of product development, the problem validation stage, we're going to concentrate on the first three of the above assumptions. These are what we call problem hypotheses.

An outside-in approach

Many startups commit their first capital mistake at this stage by not spending (enough) time to learn more about the problem hypothesis. These teams use an inside-out approach in which the vision stems from an internal requirement, and they decide to build a product based on the opinion of one or more team members, maybe a couple of close friends.

This approach is entirely obverse to the principles of lean product development because, at this point, we cannot know anything about who else has this problem or this problem is meaningful enough to address.

On the other hand, an outside-in approach dictates that we should first talk to our potential customers before planning and building anything. Steve Blank, the author of The Four Steps to Epiphany, once famously said that "no plan survives first contact with customers". Blank urges his readers to "get out of the building" and start talking to potential customers about the problems (not the solution!) we are aiming to solve. Let's see how we can do that in practice.

Knowing your target customers

Ok. We're standing outside our office building in the warm summer sunshine. We have an assumption that other people wish to have a solution to the problem we have identified. We want to talk to people about this. But with whom? The elderly gentlemen playing chess in the shade? The skater girl whose head is covered by gigantic headphones? Or the businessman reading today's newspaper?

We might feel, sensibly so, that not all of them will be affected in the same way by the problem. Because of their social background and prevailing circumstances, they're going to have very different opinions of the problem. The opinion of chess playing gentlemen might not be as relevant to us as the skater girl because the problem does not directly influence them. But we can be confident that they will have a point of view. And if we listen to them, they might easily throw us off track.

The businessman reading the newspaper might be a potential customer. It is easily conceivable that he travels to work by bike or an electric scooter. But we cannot be sure of this. We might get helpful information from the discussion, but it's more likely that we're going to hit a dead end. Our time is valuable, so it's worth investing in conversations that are more likely to lead to valuable insights.

As you can see, it's crucial to precisely define whose opinions we are interested in before talking to people. About which problems do we want to learn more? The best tool for this job is the user persona.

Personas

Creating personas is something you might have already seen in other fields, such as UX design (user personas) or marketing (buyer personas). These fields use personas at a later planning phase. In product development, they proved to be a valuable tool in testing our assumptions about our target market in a much earlier stage.

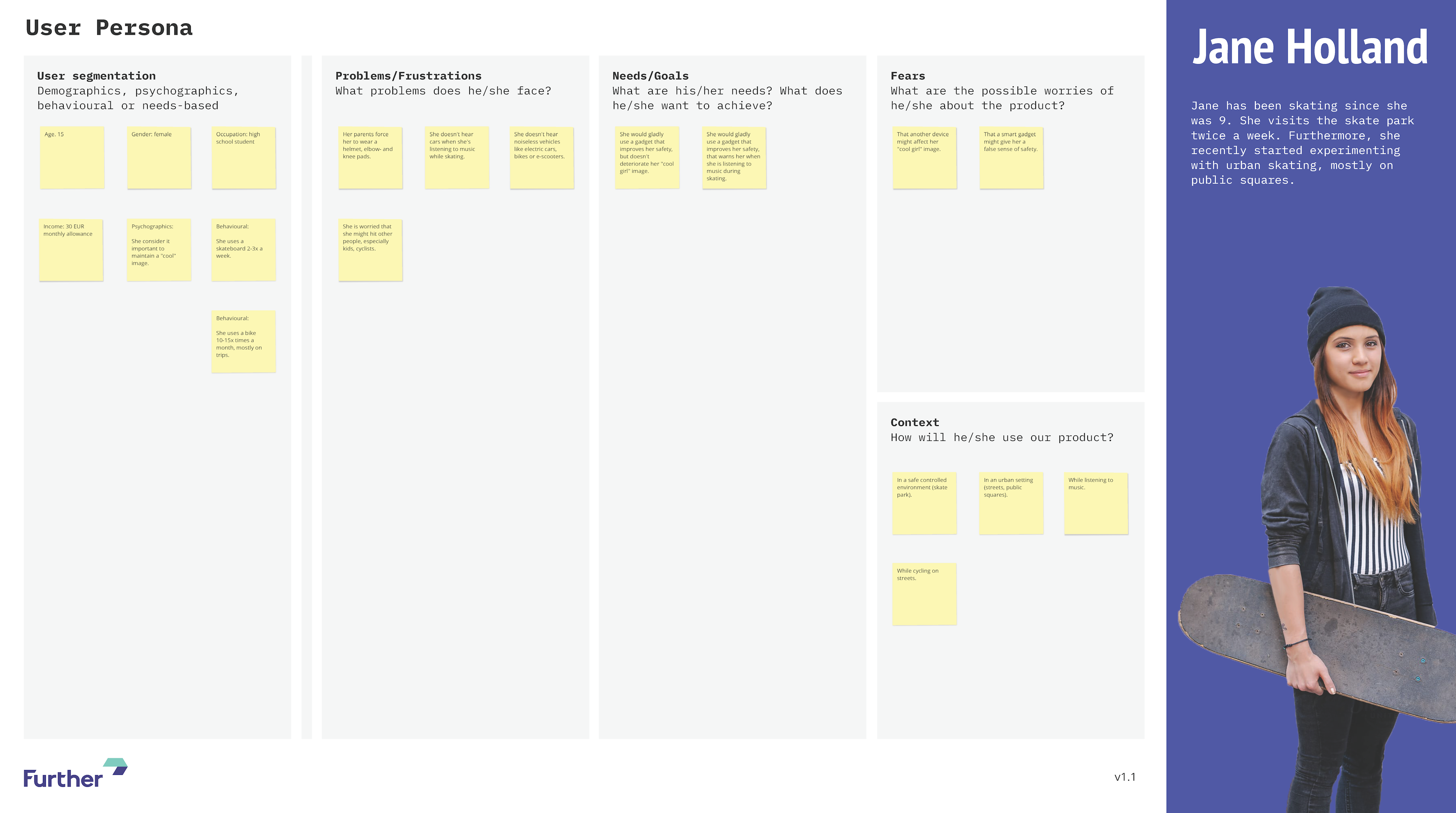

I'll detail personas in a later article. For now, let's take a look at what a persona has to contain:

- Name

- Representative photo

- Short bio

- Job title

- User segmentation (demographics, psychographics, behavioural, needs-based, etc.)

- (Assumed) problems and pain-points

- (Assumed) goals/needs

- (Assumed) fears

- Context (where can he/she face this problem, where will he/she use the product)

I need to mention that before talking to potential customers, we cannot be sure how a persona should look. At this stage, we're only assuming who they might be. It could happen that we initially targeted a specific customer group. Still, as we progress with the development of our product, we realise that we engaged a completely different type of customer. The change and evolution of personas are not only to be expected but even likely in lean product development. So feel free to adapt your personas along the way.

In our case, an example of a persona might look like the following:

Other personas might be commuters who use an electric scooter to get to work or cyclists who go out to ride on B-roads during the weekend.

Another aspect I'd like to mention here is that users and customers are not always the same. In our case, a potential customer could be a worried mother (or father) who becomes a customer because they are concerned for their child's safety.

A different customer might be the CTO or lead engineer of a manufacturing company that makes micromobility vehicles and would like to include our gadget in their own product. Their needs are going to be different from those of the users. In such cases, it might be worthwhile to create customer personas in addition to the user personas.

By drafting our vision and building our personas, we have already taken the essential steps in our Build phase of the build-measure-learn loop.

Understanding your customers

Now that we have defined our assumptions and who our customers might be, we have arrived at the last phase of our build-measure-learn loop: the Measure phase.

Don't get thrown off by the name! Although the Learn stage is last by name, we have already seen that the whole learning cycle started with defining our hypothesis or what we want to learn. After the Measure phase, the only thing left for us is to draw the necessary conclusions.

As I already mentioned, the most helpful and most effective tool in the Measure phase is customer interviews.

Customer interviews

There are two kinds of people. Those for whom interviewing is second nature and those apprehensive about it. Being anxious is natural. Interviewing is not easy. I, too, have been reluctant to interview others. I'd much rather do "book research", like reading forums and blogs to gauge others' opinions on a subject.

In his book titled The Lean Product Playbook, Dan Olsen discusses customer interviews at length. His book gave me the final push to start talking about my product ideas with others. I still don't consider myself a good interviewer. But the very first talks already showed me that even these not so perfect 1-on-1 interviews are much more efficient than what I tried before.

I encourage everyone to cast their fears aside and approach the skater girl for an interview. Be prepared with an interview script. You don't have to swear by it and stick to every letter. Instead, treat it like a loose guideline that helps you keep your assumptions centre stage at any time and to make sure you get your answers.

Don't pitch! The goal of the interview is to collect information and gather feedback from the interviewee. Its purpose is not to pitch our (non-existent) product to them. In fact, pitching our idea will derail the interview. Interviewees will likely give us corroborating answers out of sympathy, even if they don't fully coincide with reality. Make sure you set the context for the discussion, but allow the interviewee to talk.

Be empathetic and listen to what the other person says. Every answer is a new opportunity to learn something new. These would be the critical elements of an interview to consider, but as I already mentioned, interviewing is an intricate subject, which I'll discuss in a later post.

During the interview, we might find out from the skater girl that although she would gladly use a gadget that would make her travelling safer, it's just not as important to her. Even the helmet and knee pads she merely wears because of her parents.

This information is something from which we can already learn. Is the skater girl going to be our primary customer? Or should we instead focus on her parents? This question is something that we should touch upon in later interviews. If a pattern emerges, we should create a separate customer (buyer) persona – the worrisome parent persona – who we can interview separately. This switching of personas would already constitute a pivot type, but more on pivots later.

Field observations

In some cases, conducting field observations might prove worthwhile, especially with products that depend on how the customers behave or products we expect to change user behaviour.

For our product, it might be useful to pick a spot in a coffee shop near a busy intersection and observe passers-by. How many scooters decrease their speed before the intersection? How many cyclists dismount before a pedestrian crossing? Are vehicles turning to their right, checking for cyclists or scooters in their blind spots? Do skaters travel on the road or the sidewalk?

We might also gain valuable information if we try travelling with micromobility vehicles ourselves. Try travelling around downtown and in the suburbs, where the infrastructure is less developed. Did we feel safe? What were the situations when we felt unsafe?

We must assess if we gain enough knowledge through field observations to make it worth the time invested. Or should we instead invest that time in more interviews? One thing that's for certain is that field observations cannot replace interviews. But they can, however, prepare us for an interview so that we can come up with better questions.

Customer journey map

Customer journey maps can also prove to be valuable tools in this stage of product development. A customer journey map is a collaborative tool that illustrates the journey (experience) of a user or persona through an actual narrative. They help us better understand the behaviour and challenges of our personas.

We should start by delimiting our starting and endpoints. How does the journey begin? How does it end, and how does it lead into the next journey?

We should continue by setting our scenes. A scene is a context, physical or logical, where the interaction will happen. For example, in the case of an e-commerce website, it could be the website itself, the mobile app, the call centre, or the brick and mortar shop. In our case (since there is no product yet), we can use scenes like the city street, a public square or the skate park.

Finally, we will define the user actions (what the persona does), their reactions (what perceivable change happens as a result) and the next steps (what options or challenges does the persona face now).

The customer journey map can represent an actual journey or an envisioned (coveted) journey. The latter will be more useful in the problem-solution fit stage of product development.

In my experience, a customer journey map works best when it is co-created with potential customers. It gives us an outstanding opportunity to gauge their reactions at specific points in the journey. We can even illustrate these emotions on an emotion diagram, where peaks mark positive reactions while valleys mark negative reactions.

Final steps

Now that we've seen a selection of tools to determine the validity of a problem, our final step will be to cycle back to the Learn phase of the learning loop. What do the field observations and interviews tell us? What do the customer journey maps show us? Did we find answers to our assumptions?

Here's a reminder of the three assumptions we're looking to find answers for:

- each (motorised and non-motorised) micromobility user faces this (safety) problem

- users of micromobility vehicles do not feel safe when travelling and would like to be able to travel in a safer way

- users of micromobility vehicles are not happy with the current safety solutions

If we manage to verify the validity of each assumption, we can progress to the next stage of product development. This will, however, rarely be the case. When one or more of our assumptions prove invalid, we should pivot. During a pivot, we adjust our assumptions based on our learnings so far and start the build-measure-learn loop again.

In our case, there's a high chance that not even the first assumption will survive the scrutiny of validation. How we should pivot, though, is something I will reflect upon later. For now, let's focus on how to validate our solution.

If you liked this article, download the accompanying infographic!

I want the infographic