Let's Build an Engine of Growth!

What's common in a SaaS product, a newspaper and the church? They all use the same growth engine! Bear with me. I'll explain.

We often mentioned metrics in our articles and saw that there are quite a few of them, serving a multitude of scopes. It's an impossible task to track and try to improve each one of them. Without a framework, a startup can lose a lot of time debating which one to focus on.

In my article titled How to Measure the Success of Your Startup I introduced you to Dave McClure's "Startup Metrics for Pirates" framework, which defines which metrics and in which order you should focus during your search for product-market fit.

An engine of growth is nothing more than an answer to the question: what drives the growth of our business? Similar to the pirate metrics, it defines a growth strategy and helps one understand why, when and how the business grows.

Eric Ries introduced the notion of engines of growth in the book The Lean Startup. He defined three types of engines of growth:

- paid engine of growth

- sticky engine of growth

- viral engine of growth

| Paid engine | Sticky engine | Viral engine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical metrics | Customer acquisition cost (CAC) | Churn rate | Viral coefficient |

| Customer lifetime value (CLV) | |||

| Core focus | Customer acquisition through paid channels | Providing higher value for existing customers (better service level, new product features, etc.) | Developing product features which encourage sharing |

| How to speed up growth | Improving CLV through cross-sell and upsell | Decreasing churn rate with regular promotions | Increasing network effect |

| Decreasing CAC by exploring alternative customer acquisition channels | Increasing customer satisfaction by developing alternative value propositions | Introducing rewards-based incentives |

The Paid Engine of Growth

There are two metrics that, above everything else, show if our startup is successful. The first one is the customer acquisition cost (CAC). The CAC is the sum we spend on average to acquire a new customer.

The other such metric is the customer lifetime value (CLV). The CLV is the sum that a customer spends on average during the time they are our customers. Our business model is sustainable if CLV > CAC.

If a business reinvests most of the difference between the CLV and CAC to acquire more customers, they use a paid growth engine.

Let's assume a workshop, making train models, spends $0.5 on pay-per-click advertising to sell one toy. After deducting manufacturing costs, they earn $5 on each sale.

On the other hand, a locomotive manufacturer can sell an engine for a profit of $500 000. However, they need salespeople, technical experts, and booths at trade shows and conferences to sell this engine. Their CAC is $50 000.

Both businesses can generate nine more sales if they reinvest their whole profits. If they wish to accelerate their growth, they need to either decrease their acquisition costs or increase their customer lifetime value. They can achieve the latter by selling additional products or services, such as an extended warranty period.

The Sticky Engine of Growth

Acquiring new customers is always welcome. However, as opposed to the paid engine, the sticky engine focuses on retaining existing customers.

While a locomotive company needs to constantly win new tenders to grow, a SaaS product, a newspaper or even the church focuses on keeping the users, readers and congregation. Even a small number of new customers is enough to grow.

The churn rate is the most important metric for a business that employs a sticky engine.

The churn rate shows what percentage of users we can keep in the long run. The maths is simple: our business will grow if the churn rate is slower than the rate of new customers coming in. The more significant the difference between the churn rate and customer acquisition rate, the faster the growth.

The simplest way to understand the sticky growth engine is to think of a bucket with holes. If we pour water into the bucket (– we acquire new customers), it flows away (– churn). If we pour water at the same rate, it flows away, and the level stays the same – no growth. If we instead try and patch the holes, the water level will eventually rise – growth.

We can diminish the churn rate in multiple ways. The easiest way is to deliver a quality product or service. Pay extra attention to user experience, the onboarding process and customer service.

There are also questionable ways to decrease churn. One of them is when a service provider locks you in. Remember when telco companies didn't allow you to take your phone number with you when switching providers? Or carrier-locked devices? Chip manufacturers and, unfortunately, software companies do the same when they force their clients into adopting a particular technology.

The Viral Engine of Growth

When employing a viral engine of growth, most of our marketing will be done by our users. The goal is that existing users refer our product to new customers. One of the users refers to two new users. Then, they also refer us to further users and so on. This leads to exponential growth.

Contrary to word-of-mouth, a referral system is a mandatory component of the viral growth engine. We don't leave it up to the customers to refer our product to others. Instead, it's almost an expectation that they do.

Most probably, all three engines of growth have a word-of-mouth element to them. But in the case of a viral engine, it's make or break. We'll probably employ some sort of search engine optimization in case of all engines of growth. But spending most of your effort on SEO while striving for viral growth is a sure way to fail.

We can break down viral growth into two further types: inherent and artificial viral growth.

Inherent Viral Growth

The more, the merrier! With inherent viral growth, sharing the product with others is necessary for it to work. We can observe this method with social platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram or even LinkedIn, as these services are meaningless unless your friends are registered.

Artifical Viral Growth

In the case of artificial viral growth, sharing is incentivized by some kind of reward system. Tupperware famously employed this method.

Even today, someone can still become a Tupperware representative and host Tupperware parties. A Tupperware party is where the host can present the products to their friends and neighbours. After each product is sold at the party, they receive a commission fee and free products. But apart from selling products, a Tupperware party is also a great occasion to enrol new representatives. This is borderline MLM. And yes, pyramid schemes also use an artificial viral growth engine.

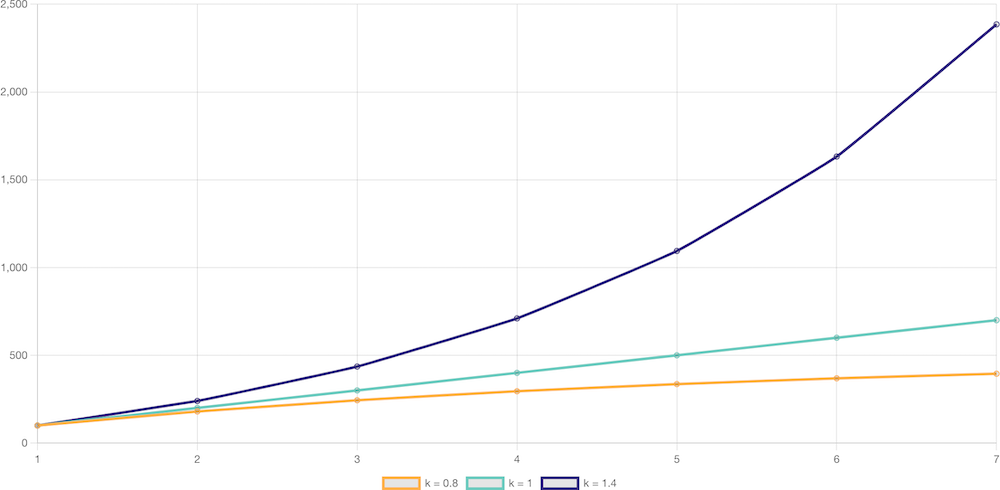

When talking about viral engines, one metric rises above everything else. This metric is the viral coefficient. This number shows how many new customers each user refers to on average. A viral coefficient of 1.4 means that we get 1.4 new customers from the referrals of a single user.

The magic number is 1. If the viral coefficient is lower than 1, our growth will eventually halt. A viral coefficient of .8, for example, means that 100 users will rise to 180, then 244, 295, and so on. Even from this short series, you can see that the growth rate is slowing. For all the other number buffs out there, the series will eventually top out at around 499 users. You're welcome.

If the viral coefficient is higher than 1, our growth will be exponential. 100 users will become 240, then 436, 710 and so on.

One Engine to Rule Them All

Can we have more than one engine of growth within a startup? Yes. For example, a viral product might also have a low churn rate.

But remember why we need these frameworks in the first place? So that we can focus our efforts on improving a specific element of our growth strategy. It's very rare that a team can follow the metrics of multiple growth engines, and even rarer that they possess the skills to operate both a viral and a paid engine. So always choose one that best suits the product or service.